Livescience

1w

309

Image Credit: Livescience

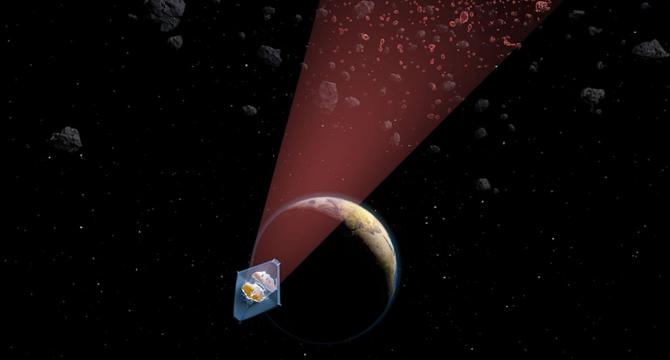

James Webb telescope spots more than 100 new asteroids between Jupiter and Mars — and some are heading toward Earth

- The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has discovered a vast population of small asteroids in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. The newfound asteroids range in size from that of a bus to several stadiums, and the discovery could lead to better tracking of the tiny but powerful space rocks that frequently approach Earth. Only a decade ago, an asteroid just tens of meters in size took everyone by surprise when it exploded over Chelyabinsk, Russia, and released 30 times more energy than the atomic bomb detonated over Hiroshima in WWII. The newfound asteroids collide with Earth 10,000 times more frequently than their larger counterparts, but their small size makes it challenging for surveys to detect them well in advance.

- Julien de Wit, an associate professor of planetary science at MIT, has been testing a computationally-intensive method to identify passing asteroids in telescope images of faraway stars. By applying this method to thousands of JWST images of the host star in about 40 light-years distant TRAPPIST-1 system, the researchers found 138 new decameter asteroids in the main asteroid belt among which six appear to have been gravitationally nudged by nearby planets into trajectories that will bring them close to Earth.

- Fresh look at archival images of the TRAPPIST-1 system led to the discovery of the asteroids that are remnants of collisions among bigger, kilometer-sized space rocks The newfound asteroids are the tiniest yet to be detected in the main asteroid belt, and JWST proved ideal for the discovery due to its sharp infrared eyes that detect the asteroids' thermal emissions. Upcoming JWST observations are expected to lead to the discovery of thousands more decameter asteroids in our solar system.

- Newer telescopes will also help uncover thousands of small asteroids in our solar system. Chief among them is the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, which will capture images that each cover an area equivalent to 40 full moons. High frequency and resolution is expected to detect up to 2.4 million asteroids, nearly double the current catalog, within its first six months. "We now have a way of spotting these small asteroids when they are much farther away, so we can do more precise orbital tracking, which is key for planetary defense," says one of the researchers.

Read Full Article

18 Likes

For uninterrupted reading, download the app